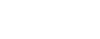

Amelia Edwards

When she first arrived in Egypt in 1873, Amelia Edwards was already a seasoned writer, with several history books, novels, and two travelogues under her belt. She hadn’t, in fact, intended to turn her pen to Egypt, but when a walking tour in France was kyboshed by heavy rain, she and her companion Lucy Renshawe set sail for Alexandria.

Image: Peggy Joy Egyptology Library

The pair spent two days in quarantine, before journeying onto Cairo, where Edwards got her first glimpse of the Great Pyramid:

‘The effect is as sudden as it is overwhelming. It shuts out the sky and the horizon. It shuts out all the other pyramids. It shuts out everything but the sense of awe and wonder.’

In mid December, Edwards, Renshawe and a troupe of fellow travellers set sail down the Nile, taking in the Saqqara Necropolis and Mit Rahina, Luxor, and Nubia. Edwards immortalized the journey in A Thousand Miles Up the Nile, an instant bestseller illustrated with her own paintings and drawings.

Although today it is quite possible to get from Cairo to Aswan and beyond over land, or even by air, in Miss Edwards' day – as in ancient times – the only way to travel was along the river. Image: Peggy Joy Egyptology Library

As their voyage progressed, Edwards became increasingly frustrated with the vandalism and exploitation of ancient Egyptian monuments, heralding many of our contemporary conversations about cultural heritage. ‘The tourist carves (the monument) all over with names and dates,’ she wrote:

‘The student of Egyptology, by taking wet paper ‘squeezes,’ sponges away every vestige of the original colour. The ‘collector’ buys and carries off everything of value that he can get… The Louvre contains a full-length portrait of Seti I, cut out bodily from the walls of his sepulchre in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings. The Museums of Berlin, of Turin, of Florence, are rich in spoils which tell their own lamentable tale.’

Edwards returned to England committed to on-site conservation of the Egyptian monuments, co-founding the Egypt Exploration Fund in 1882 to support conservation expeditions. Some mocked Edwards’ work; Samuel Birch, keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum, sneered at her ‘sentimental archaeology.’ But Edwards’ legacy far outweighs any derisory sexism of her time. The Egypt Exploration Fund remains a leading archaeological non-profit to this day, while the Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology is a professorial chair at University College London.

Above, right: Front cover of the second edition of Edwards’s 'A Thousand Miles Up the Nile', perhaps the most celebrated of all the many such accounts of journeys through Egypt.

Marianne Brocklehurst

Marianne Brocklehurst was born in Macclesfield, England in 1832, the daughter of a wealthy silk manufacturer. She first travelled to Egypt in 1873 together with her partner, Mary Booth, and would return numerous times over the ensuing years.

Image: Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

On that first trip, Brocklehurst and Booth met Amelia Edwards, and joined her expedition along the Nile. Brocklehurst and Edwards shared a plucky adventurousness, but did not have quite the same scruples about the integrity of Egyptian heritage. For Brocklehurst, the best way of generating interest in Egyptology back in England was to acquire as many objects for display as possible, by whatever means. She actively sought out information on unofficially-discovered tombs and secured a number of pieces illicitly – including the star turn in her collection, a brightly-coloured mummy case belonging to a chantress named Shebmut, which she acquired on a furtive nighttime expedition and bribed out of the country.

After Brocklehurst’s fourth visit to Egypt, she decided that her collection should be put on public display and built the West Park Museum in Macclesfield to house it. Her collection remains there to this day, with a particular emphasis on female Pharaohs and Gods.

Above, left: Two sketches by Brocklehurst documenting the discovery of the burials of over 150 priests of Amun, now known as the Bab el-Gasus cache. Above, right: Brocklehurst’s drawing of the colossi of Memnon (twin statues of Amenhotep III) at Luxor, and a scarab depicting the pharaoh and his wife, Tiye, which she purchased in Qena ‘for 12 shillings, an old railway reading lamp and a small bottle of castor oil. Afterwards Dr Birch wanted to buy it for the British Museum.’

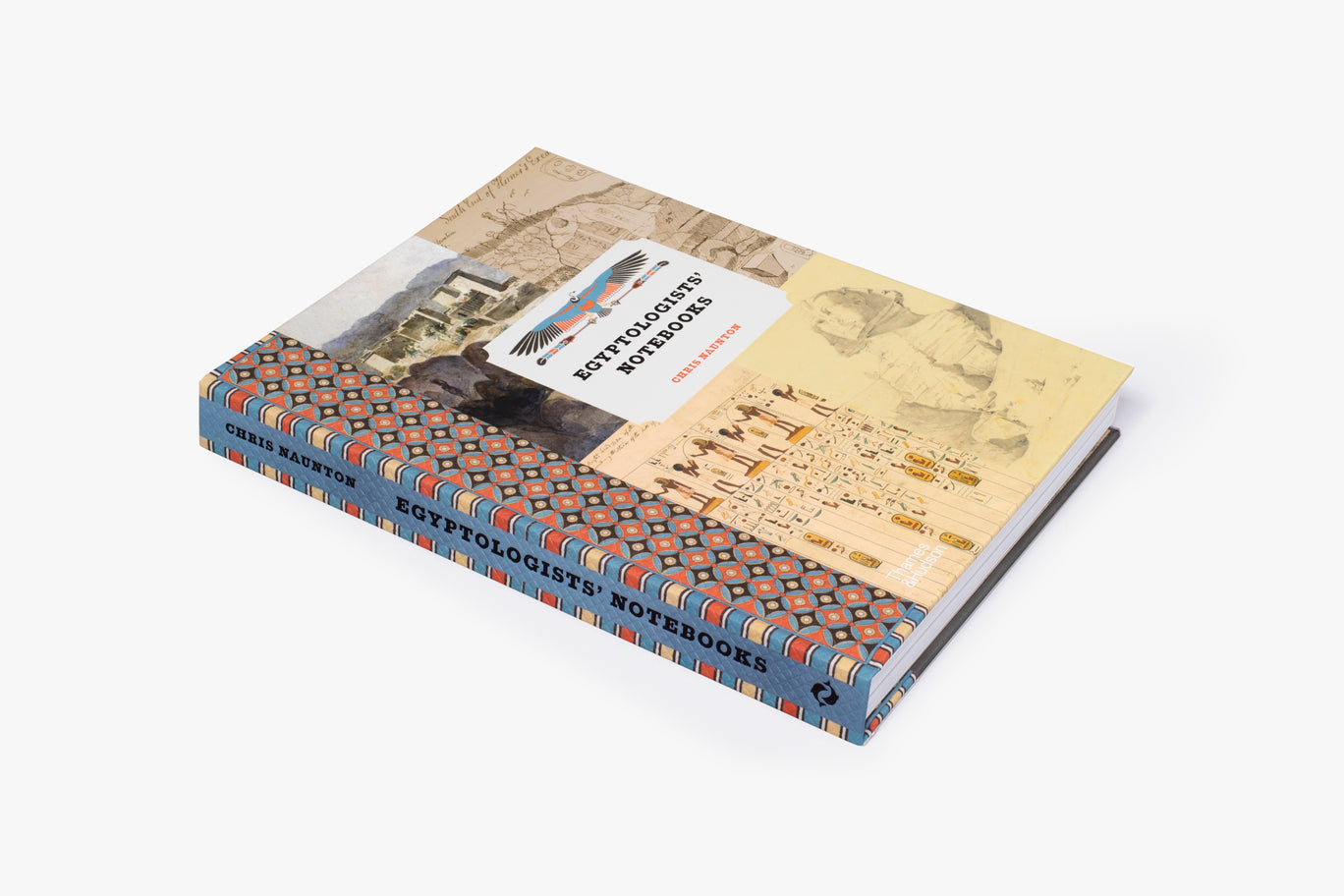

Nina de Garis Davies

In 1906, Slade School graduate Anna (Nina) Cummings went on holiday in Egypt and met the minister, Egyptologist and fellow artist Norman de Garis Davies. They married the following year and settled down together near the Theban Necropolis, where Norman was working on facsimiles of Egyptian wall paintings for the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Just weeks after their wedding, Nina set out with Norman on expedition, initially working as an unofficial assistant, before graduating to a part-time role. Often signing their work together as ‘N. de Garis Davies’, the pair worked prolifically at the sites of Amarna as well as the cemeteries of Thebes.

Nina Davies’ facsimile of a detail of a scene showing the bringing of produce of Kharga, Punt, and the Delta, including wine, papyrus, oil, and honey and nuts with monkeys, to storehouses. From the tomb of Rekhmira. Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The extraordinary precision and accuracy they brought to their reproductions were the result of meticulous scrutiny of every minute detail of every tomb wall, from every angle. Although photography had advanced by the early 20th century, the Davies could see much more than the camera could – not only what was there on the walls, but also the elements now damaged or lost that should have been there.

Later, the Davies would also work on Egyptian Grammar, the standard point of reference on Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Today, their drawings survive in various institutions around the world, most particularly the Met, and constitute one of the greatest pictorial documents of Ancient Egypt.

Words by Eliza Apperly